Joe D'Ambrosio's story offers reasonable doubt about Ohio justice.

Joe D'Ambrosio's father believed in the virtue of work. For decades, he punched the clock at General Electric, installing liners in train engines. He taught his only son that a job provides two rewards: a paycheck and self-respect.

Keenan (left) and Espinoza (center) both had checkered pasts. The only blotches on D'Ambrosio's record were two DWIs.Dad always told me, You work. I don't care if it's flipping burgers, you work,' D'Ambrosio recalls.

He intended to abide by his late father's credo, following an honorable discharge from the Army in 1985. The North Royalton native returned home after a four-year hitch that saw him awarded the Good Conduct and Army Achievement medals for his skill as a mechanic. He figured finding work in an auto shop would be easy. He found misfortune instead.

D'Ambrosio learned that his Army mechanic's certification carried no value in the private world -- he would need two years of training to become recertified. The $27,000 tuition may as well have been $27 million.

For the next three years, he pumped gas, installed car alarms, mowed lawns. He earned a paycheck, but pride proved more elusive. So he drowned his frustration at the Saloon, a Coventry Road bar that offered cheap drinks and the comfort of regulars.

D'Ambrosio had little else on his mind on August 31, 1988. At some point that Wednesday night, a voice pierced the pub's din. A gaunt man with a mustache said he was a foreman of a landscaping crew and asked if anyone needed work.

Landscaping sounded as good as anything else to D'Ambrosio. He introduced himself to Ed Espinoza, and the next day he met with Espinoza and Michael Keenan, owner of Sunshine Landscaping. Keenan hired him on the spot.

Less than a month later, he, Espinoza, and Keenan were in jail. The following February, D'Ambrosio was sentenced to death after a three-day trial -- likely the shortest capital case in state history.

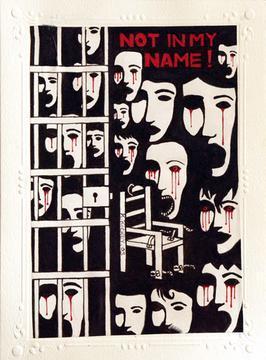

Like almost every one of Ohio's 201 death-row inmates, D'Ambrosio claims innocence. But unlike the others, there are people who actually believe him. Inside the state Public Defender's Office, he is known as "the unluckiest man in the world." Two Ohio Supreme Court justices have argued his life should be spared. Death-penalty critics contend his case pulses with reasonable doubt.

D'Ambrosio appreciates the support. Still, he wishes he didn't need it.

"If I hadn't been in that bar that night and met Espinoza, I wouldn't be here now."

In September 1988, Tony Klann was 19. He looked younger. A flop-cut topped a boyish face; a rattail hinted at a free spirit. He scraped by as a deli stockboy and mowing lawns for Sunshine Landscaping. He used the money to party on life's fringes.

A haphazard student who struggled to finish high school, Klann had good attendance at the bars in Coventry and Little Italy. His friends were anyone with extra beer or pot and a couch to crash on. His girlfriend danced at a strip club. To Klann, midnight felt like noon.

"He liked people who were kind of living on the edge," says Richard Klann, Tony's father.

Richard and his then-wife, Diane, adopted Tony and his sister when they were toddlers. The Klanns represented the fifth and last set of parents for the siblings, a warm ending to their bleak foster-care odyssey.

Tony grew up "happy-go-lucky" despite a learning disability that his classmates teased him about, Richard recalls. As he grew older, he itched for freedom, leaving home at 18 with few plans and less money. "I emancipate myself," he wrote in a note to his father.

But it was a more practical Tony who met Richard for dinner at a Mayfield restaurant on Tuesday, September 20, 1988. He said he wanted to escape the drug-and-booze scene and start fresh. He talked about setting up his own landscaping business, an idea his father heartily endorsed.

"He was doing his own thing, finding his way," Richard says.

Cleveland homicide detectives Ernie Hayes and Mel Goldstein received word of a body floating in Doan Creek on Saturday afternoon, September 24. They found the victim's neck sliced from ear to ear; two puncture wounds exposed his trachea. His face, chest, back, right forearm, and left wrist were slashed. Half his forehead was bashed in. Most of his blood had drained away, turning his skin bone white.

The detectives scoured the creek bank near Martin Luther King Jr. Drive and East Boulevard for clues. "There was nothing there," Goldstein says.

In the late 1980s, the Cleveland homicide unit shone like few others, boasting an 80 percent "solve rate" on murder cases that ranked among the best for metro police forces nationwide. Success came as veteran detectives ran hard on the long leash let out by their superiors.

"You were free to do whatever you needed to do, so long as you got results," Hayes says.

Detective Leo Allen took over the case on Monday, September 26. His legwork bore results in a scant three hours.

Allen visited the Cuyahoga County morgue that morning on another case and wound up talking with three men -- Paul Lewis, James Russell, and Adam Flanik -- who were there to identify the body of a friend pulled from Doan Creek. None of them could be located for this story.

Lewis sometimes let Tony Klann stay at his Little Italy flat. Like Flanik and Russell, he knew Ed Espinoza and Michael Keenan from the neighborhood bars. He also had spoken to D'Ambrosio on occasion.

Lewis, nicknamed "Stoney" for his love of weed, said he last saw Klann alive on Friday night, September 23. He and Keenan bumped into each other around 8 p.m. that evening at the Saloon, where they had a drink before driving down Coventry Road to Coconut Joe's. Both bars have since closed.

Read more of this very long article on: http://www.clevescene.com/2001-11-22/news/unluckiest-man-on-death-row/